Do you find yourself needing a refresher on how to explain each of the pedal functions to your students? Interested in seeing examples of music that use each? Look no further!

The three pedals on the modern piano each provide a distinct function, and they can completely change the sound of a passage when used tastefully. While there may be differences of opinion in when and how to apply them, each pedal tells a unique story.

The Soft Pedal (Una Corda Pedal)

The soft pedal, which is to the far left, is also commonly known as the “una corda” pedal. You might see this abbreviated with “u.c.” in some scores, which stands for una corda. This pedal shifts the strings to the right so that one less string is struck, which creates a very different sound! Cristofori’s original soft pedal mechanism reduced the hammers to striking only one of two strings, which is why the technique is named una (or one) corda. Fewer strings also mean less sound, hence the nickname “soft pedal.”

However, I encourage students not to simply use this pedal to make it easier to get a softer sound. Rather, it should be used to create a special sound. Most of the time, it’s possible to play in a way that creates a very soft sound without the soft pedal, and this pedal also changes the timbre by creating a blurry, muffling effect. So, if a student wants to use the soft pedal, I ask them if it really fits the passage of music and what they are trying to achieve musically.

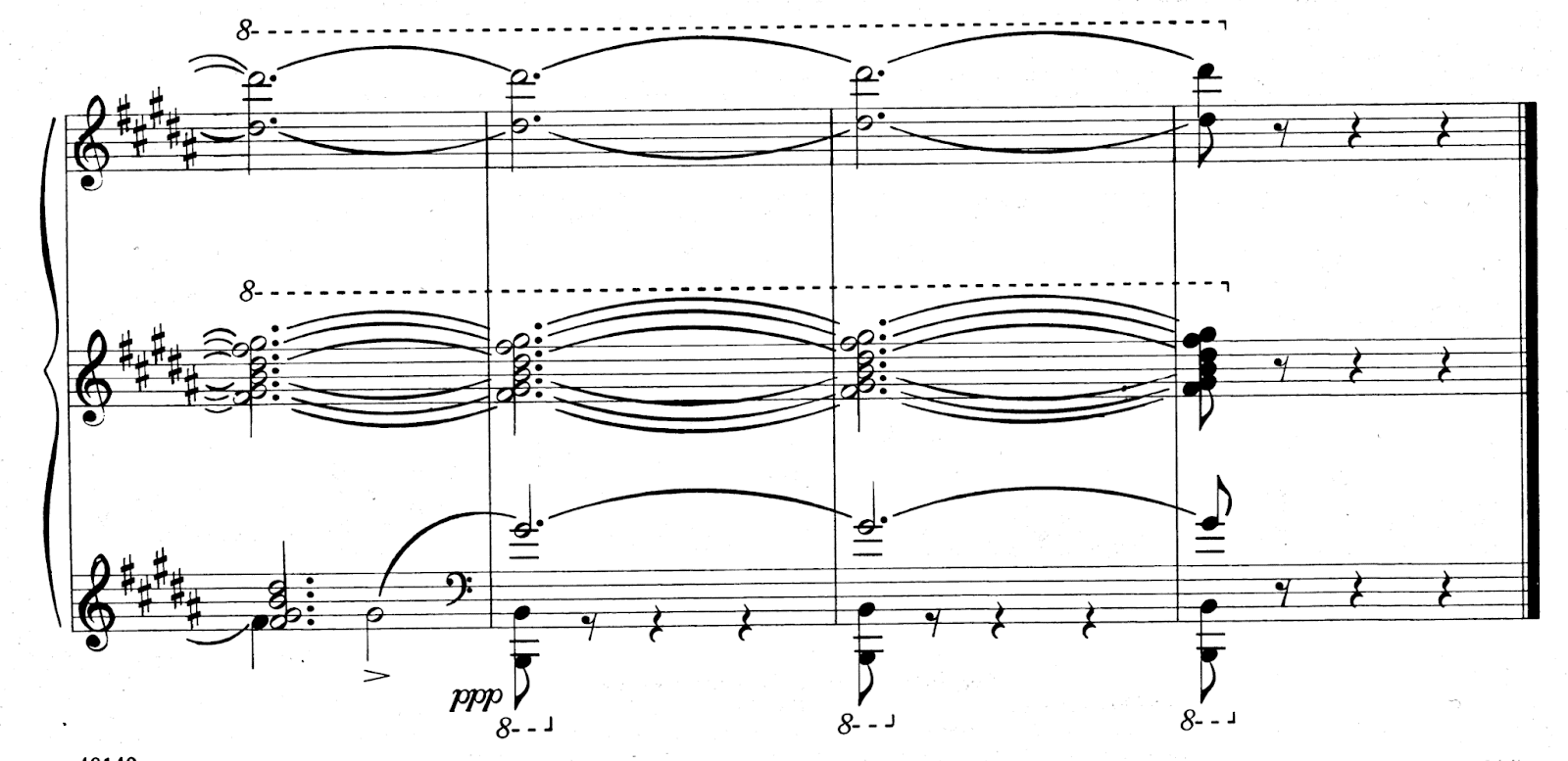

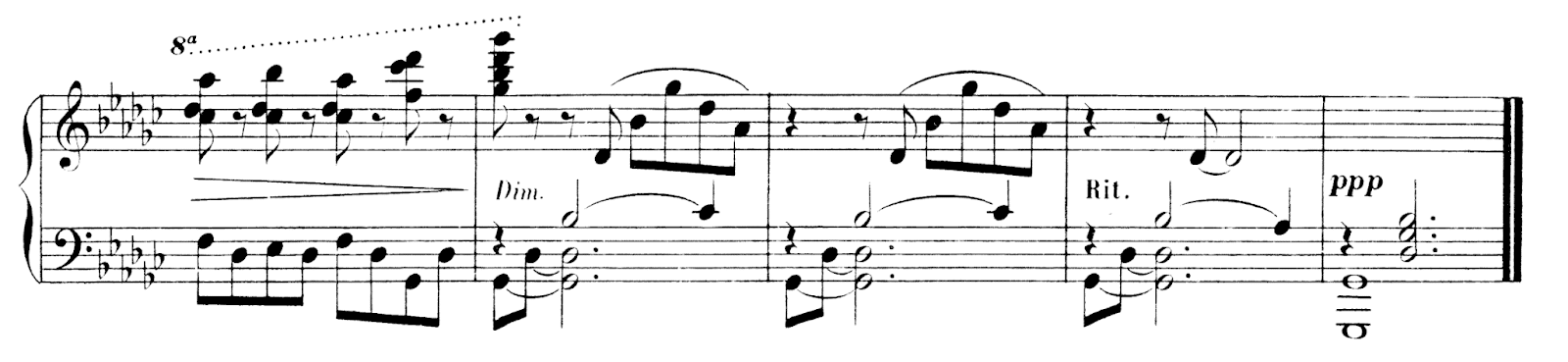

I often find that impressionistic music has many opportunities to use the soft pedal to create a wider palette of sounds. And since a blurred sound is more stylistically appropriate in that style, the una corda fits right in! For example, the end of Lili Boulanger’s D’un jarden clair provides an excellent opportunity to add a soft and mysterious quality to the closing.

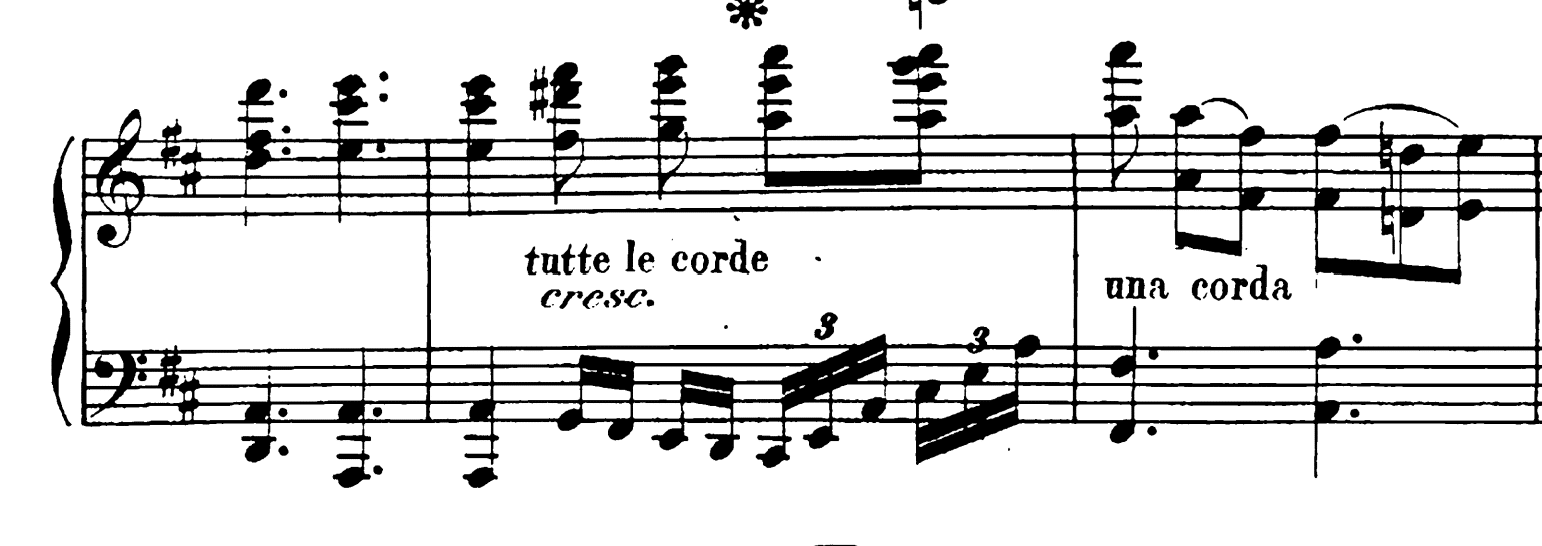

In fact, some composers have marked una corda in the scores, even though they also mark louder surrounding dynamics. Here is an example from Beethoven’s Hammerklavier Sonata, Op. 106, where he indicates a crescendo that is then followed by an una corda marking. Perhaps this means to play softer; or perhaps, Beethoven intended a different type of sound completely.

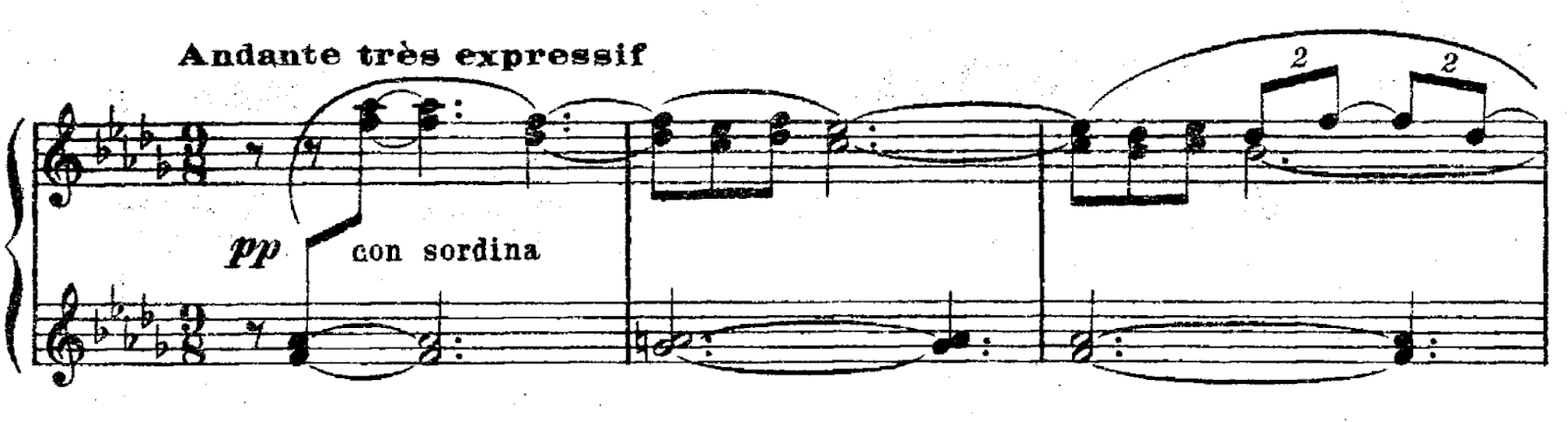

The abbreviation “t.c.” (tre corde) is sometimes used to indicate an end to una corda. In many cases, though, the pianist may simply need to use their ear and best judgment to decide when to lift the soft pedal. In Debussy’s Claire de Lune, he indicates con sordina at the beginning but never a release; taken literally, this would mean soft pedal for the entire piece, but pianists may interpret this to mean soft pedal throughout the piece, as needed or desired.

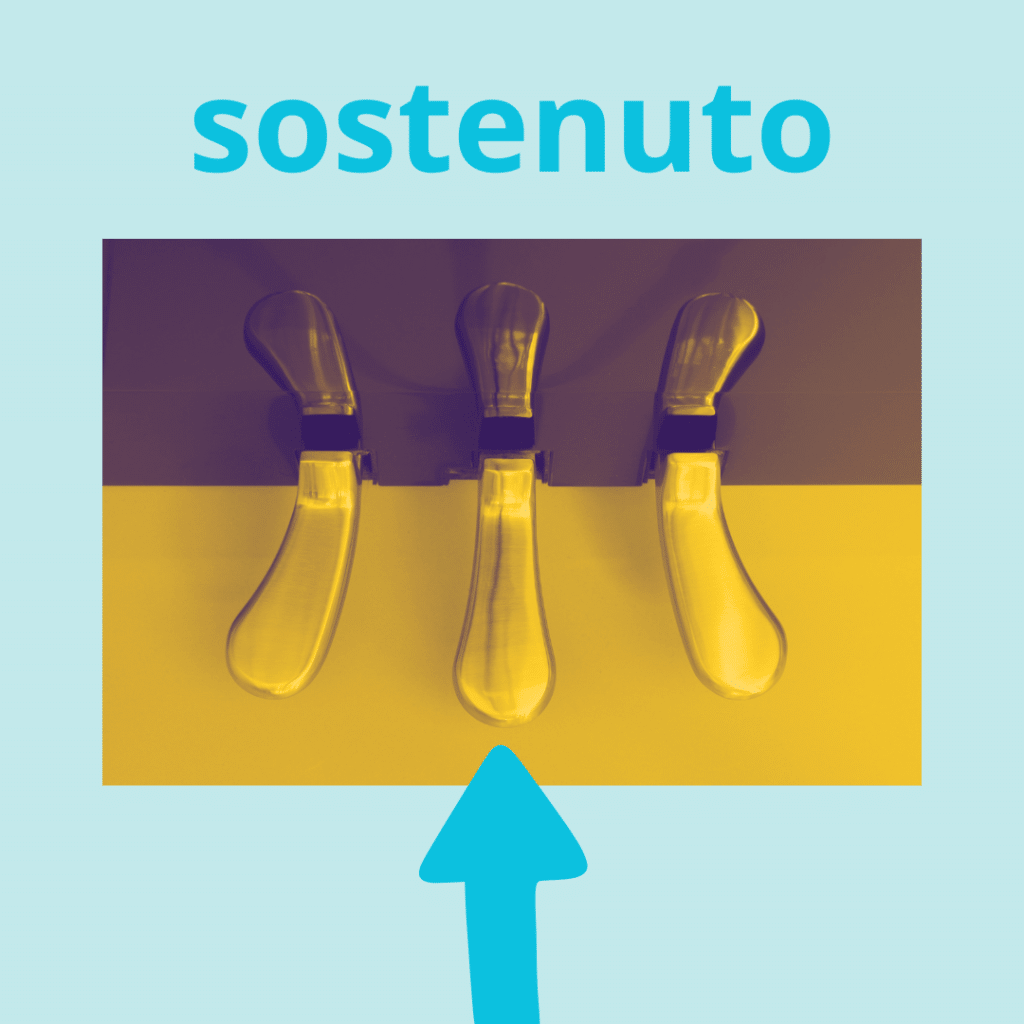

The Sostenuto Pedal

The sostenuto, or middle pedal, is the one everyone forgets about! It is only seldom used, and it can be difficult to pull off accurately. On most pianos, this pedal allows you to sustain notes below middle C in the lower half of the piano. So, you can sustain a low note while playing fast passagework in the upper register, and the passagework remains clear. Please note: Sometimes, on upright pianos, the middle pedal is a practice pedal that lowers the volume for quiet practice.

With the sostenuto pedal, you must remember to first play the note (or notes) you want held, then depress the pedal while they are still held. The timing of this can be tricky, so it may be hard to use this in a fast passage, especially if you are combining it with other pedal work.

The sostenuto pedal can be particularly helpful if you want a ringing bass note with some kind of figuration on top. You might see this type of pedaling notated as Sos., Sost., or S.P. in your score, and it’s mostly commonly found in more contemporary works. However, I have found other uses for this, even in Classical sonatas!

Look at the last two measures of Ravel’s “Sonatine.” This is a great use of the sostenuto pedal, as the low grace note gives the pianist time to catch the low notes before depressing the pedal and moving on.

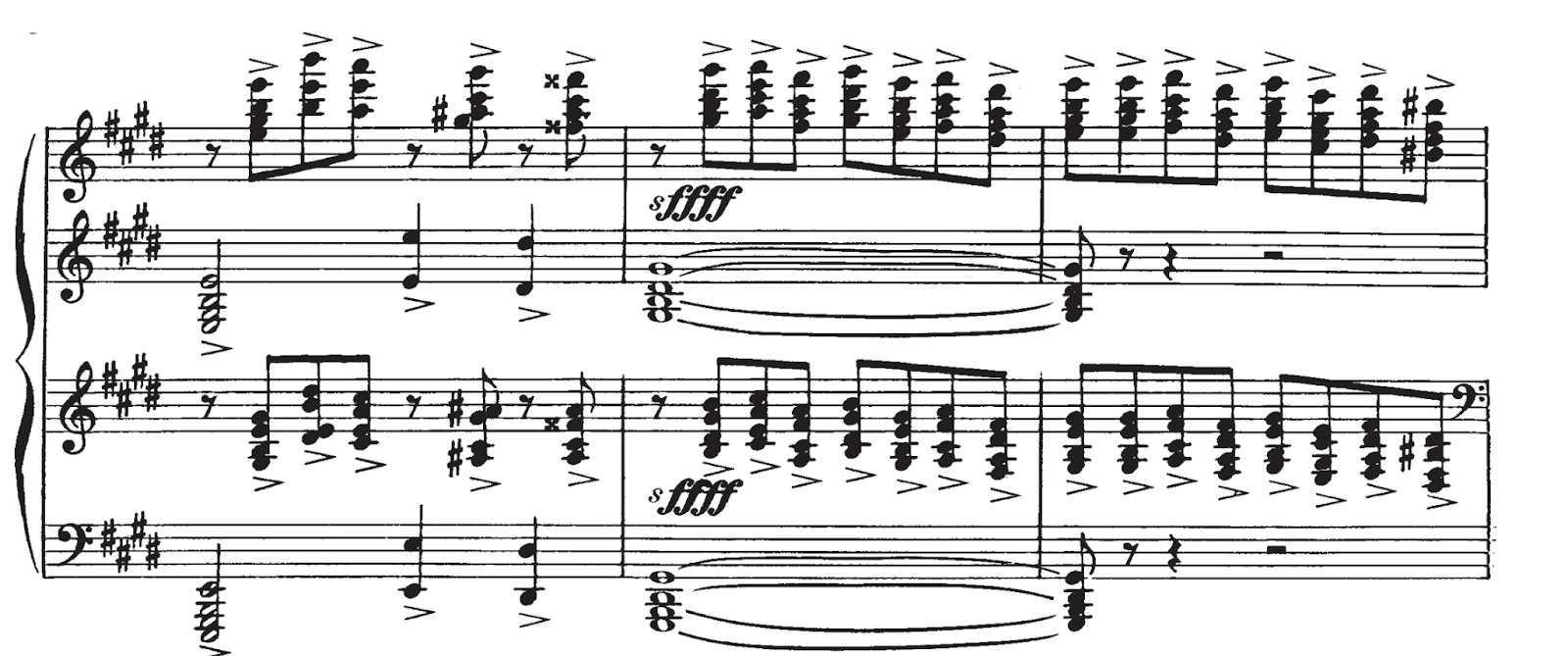

Also, observe the texture in Rachmaninoff’s well-known Prelude in C-Sharp Minor. Although una corda is not explicitly requested here, using it can allow a much cleaner sound at the sfff marking.

The Sustain Pedal (Damper Pedal)

Last but certainly not least, the sustain pedal lifts the hammers so the strings can vibrate freely. This simple but amazing trick means that the sound you play continues to ring out until you release the pedal or until the sound decays.

The sustain pedal, also called the damper pedal, is often overused—I am guilty of this myself! In music that needs more clarity (particularly those of the Baroque and Classical periods), less is more! A little pedal can go a long way.

On the other hand, using the sustain pedal can add much richness and color to music, especially if the style or piece implies that harmonies should be layered or connected. Romantic music, in particular, is a prime example of a style that requires good pedal technique, as most pieces would sound strange without it.

For example, this lovely finish to Mel Bonis’ Carillon Mystique includes broken chords. Using the pedal here and changing with each new chord creates a smooth sound.

Wrapping Up

To summarize, the pedals on a piano provide so many opportunities to explore new sounds, colors, and techniques! While pianists should be conscious of stylistic considerations, it is also important to develop a keen sense of intuition and a strong ear to know when and where to use each pedal.

Dr. Olivia Ellis teaches piano, group piano, pedagogy, and chamber music at Messiah University in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania. She’s an editor for Piano Magazine and has published several books including the Easy Piano Lead Sheets and Chord Charts series. She’s constantly creating new activities and games to teach concepts, and loves helping other teachers find their niche.