One of the most important aspects of teaching and interpreting music involves correctly using articulations. Very few things affect the character and energy of music more than how we physically attack or touch the keys. Articulations are a big deal!

They can also sometimes be a bit mystifying due to changes in the meaning of symbols over time. Even when we know the correct context, we occasionally have to use our best musical judgment to bridge the gaps. It can get complicated! Here we give the basic definition of each articulation as it would apply to pianists and explore some special cases to get you started.

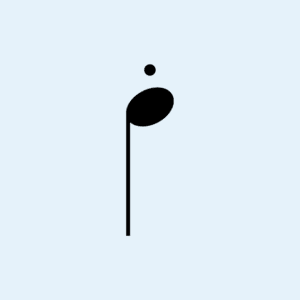

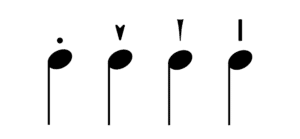

Staccato

The literal translation of the Italian word staccato is “detached,” and in music, it indicates to shorten the duration of a note. Staccato markings first appeared in music during the late 17th century and are most commonly indicated with a dot placed above or below a note.

However, prior to the mid-19th century, dots, wedges, and dashes were all used interchangeably to indicate staccato.

Because of this, it’s important to remember that, in early music, a wedge or dash might just mean to play it short. Consider the period of the work as well as the surrounding section to determine the best touch.

Staccatissimo

It wasn’t until the second half of the 19th century that the solid wedge shape (formerly a staccato) took on the new permanent meaning of a shorter staccato called Staccatissimo. This articulation is played very short with a pointed sound. On the piano, you would often play this with a very sharp attack using the tips of the fingers.

Slur

A slur is a curved line that tells the performer to play the notes above or below it smoothly without separation. In piano music, slurs are also often used to indicate phrases and where to appropriately lift the hand to create breaths in the music.

One kind of slur, called the two-note slur, occurs frequently in all kinds of music, and we usually treat it with several standard rules in order to create a beautiful “musical sigh” between two notes.

- Two-note slurs should generally have a slight emphasis on the first note.

- The second note should be lighter and usually a bit shorter. It’s okay to “cheat” the second note and not hold it for the full duration.

- The arm/wrist should descend on the first note and lift lightly on the second note to achieve this effect. Think about using arm weight to fall into the first note, then simply release with an upward motion as you play the second.

It is also important to note that many classical composers, such as Mozart, based some of their slurs on string-instrument bowing even when they were writing for keyboard instruments. There are instances in classical period music where short slurs will need to be thought of in the context of a longer phrase instead of many short, deliberate slurs.

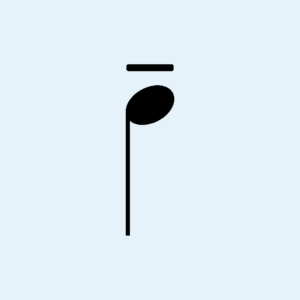

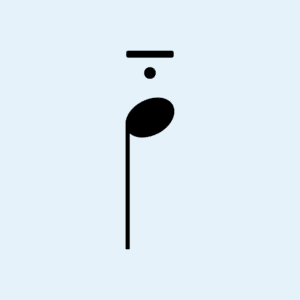

Tenuto

Tenuto is notated with a horizontal line above a note. The most basic definition of tenuto is to hold a note for its full value. However, there are several additional ways to interpret this symbol. It sometimes means to slightly accent or emphasize a note, or it can even mean to play the note slightly longer or with rubato. Contemporary composers will also often use the tenuto marking to indicate a melody that needs to be voiced louder than the surrounding figuration. However, playing the full value of a note is a great place to start, and then it is up to the performer to look at the surrounding context for additional clues. For example, is there a marked rubato that might indicate holding out the tenuto past the full value?

Portato

This articulation looks like a dot with a horizontal line above it and means to play somewhere between legato and staccato or “semi-legato.” Some people refer to this technique as portamento, but the word portamento is more commonly associated with a sliding technique used by vocalists and string players. Somewhere along the way, the term portamento became synonymous with portato in keyboard music. I personally prefer to use the term portato and have heard other experts discourage the use of the word portamento in the context of keyboard music.

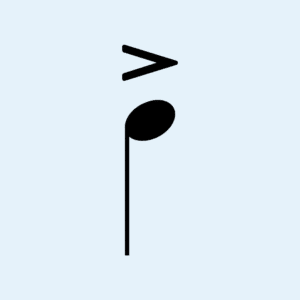

Accent

Accents, notated with a sideways wedge shape simply mean to make a note louder than the surrounding notes. However, the loudness of an accent will vary based on the stylistic period, dynamic level, and how it fits with the phrase and character of a composition. A classical accent of Mozart or Haydn could generally be played more lightly than that of Beethoven or Romantic and 20th-century composers. And, an accent in a section with piano dynamics will be quieter than an accent in a forte section.

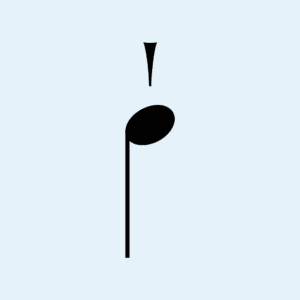

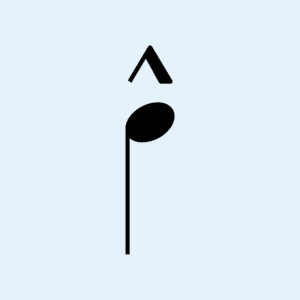

Marcato

Marcato has a similar definition to accent but is generally regarded as louder or more forceful than a standard accent. In addition to a more forceful attack, the sign can also mean to play the note shorter. It is notated with a “rooftop” accent and comes from an Italian word that means “hammered.”

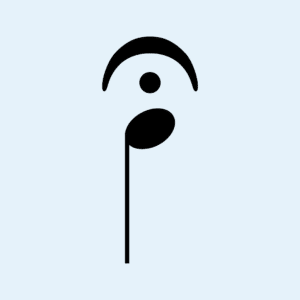

Fermata

Fermata comes from the Italian word fermere, meaning to stay or stop, and means to hold a note or rest for longer than the normal duration. The amount of time a fermata is given is up to the performer or conductor, but it is common to make the duration at least one and half times as long as the written note value.

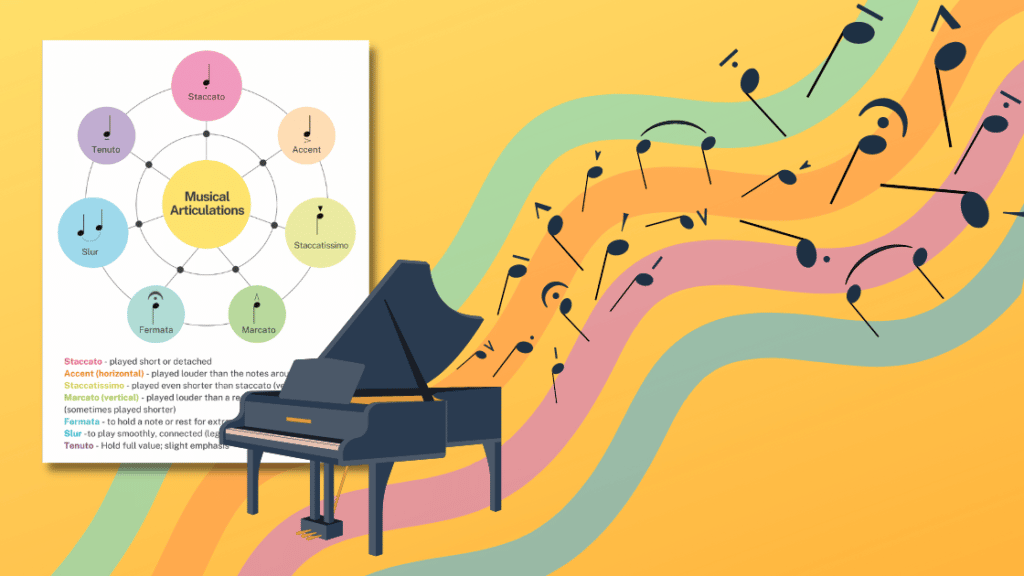

Here is a quick reference chart to help you remember some of these articulations. If you are a teacher, it is a handy guide to give to your students or leave on your piano. You can get this and more free resource downloads here.

As you are interpreting articulations, it is important to consider the historical and stylistic context of the symbol. For example, an accent in a very soft piece may not be as loud as one found in a forte passage. And, a staccato in a classical sonatina is likely more light and graceful than those found in a 20th-century piece. Once you have thoughtfully considered these, make sure to use your ear for the final judgment in order to make the best musical decision!

Nice article and the chart will be very useful for students! Thanks!

Thanks, Sandy! Glad it is helpful!

So glad it will be helpful to you and your students!😄